Home > Arkansas > Arkansas Environment > Feral Hogs are Arkansas Agriculture’s No. 1 Enemy

Feral Hogs are Arkansas Agriculture’s No. 1 Enemy

It’s a problem without a solution. Or it seems that way, at least. When it comes to tackling the issue of feral hogs in Arkansas, farmers, ranchers and others are facing an invasive species that could be considered enemy No. 1 to agriculture.

“It’s a very big problem,” says Preston Scroggin, director of the Arkansas Livestock & Poultry Commission. “These wild hogs will get on the levees and tear up the system. They get into the pine tree plantations and root up the trees, or get into the cattle pastures and tear them up.

“We’ve had reports of pretty severe damage. We’re estimating that feral hogs are probably doing $30 million to $50 million annually in damage to the state.”

Wild hogs are not native to North America, but they’ve been in the United States since they were introduced to the Southeast in the 1500s. They are troublesome on many fronts, as they compete for food resources, destroy habitats through rooting, and will eat ground-nesting birds, eggs, fawns and young livestock. Feral hogs also carry bacteria, diseases and parasites.

And they’re practically impossible to get rid of.

“You’ll never eradicate them,” Scroggin says, “but you can try to control them.”

Very, Very Smart

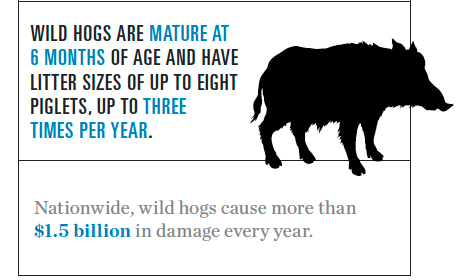

The traits that make domestic pigs ideal livestock are the same ones that make feral hogs a dangerous threat. Hogs are considered the smartest farm animal with the highest body to brain size ratio. They are extremely resilient and resourceful when it comes to survival, finding ways to cool themselves since they don’t have sweat glands and even rooting for food when necessary. They also have multiple litters each year with the largest number of offspring per litter of any other farm animal.

It’s the same for their kin in the wild, which explains why they’ve been such a nuisance for farmers such as Randy Haynes. He grows mostly corn and soybeans on his 1,500-acre farm west of Wilmot. His battle with feral hogs began about 30 years ago.

“From the first planting, they’ll come in and root down finding the seed,” Haynes says. “You’ll come back the next morning and half your field is plowed up, then you have to go back and replant. Of course, that costs money. It’s just nonstop.

“When you’re irrigating, they’re out there rooting around your pipe and moving it around. Then when the corn starts to silk real good, they go crazy over it. They’ll break it down, eat about half of it and go to another. It’s just unbelievable.

“They’re just a hungry machine that loves to eat, and they’re very, very smart. You put a little pressure on them and they’ll disappear for a short while, but when you least expect it, there they are again.”

Control Is Key

As Scroggin mentions, there are ways to stem the problem of wild hogs even if eradicating them completely is unlikely. The Arkansas Game and Fish Commission recommends trapping them in large numbers using corral-type traps, adding that “shooting one or two hogs from a group, or sounder, will cause the rest to relocate, wasting any effort land managers have made in baiting trap sites.”

Also, in 2013, the Arkansas General Assembly passed Act 1104, which prohibits the possession, sale and transport of live feral hogs. The law is in response to hunters transporting hogs to properties for sport hunting.

“These hogs are moving enough on their own,” Scroggin says. “They don’t need any help.”