Home > Colorado > Colorado Farm to Table > The Crisis Hotline Colorado Farmers Rely On

The Crisis Hotline Colorado Farmers Rely On

In partnership with: Colorado Department of Agriculture

For many Colorado farmers, farming is not just a job, but a way of life. Farms and ranches have been passed down through generations, and it’s the responsibility of the newest generation to keep the operation thriving, prospering and growing. But farming, unfortunately, is an unpredictable way of life, with many uncontrollable challenges that accompany it, including weather and natural disasters, price fluctuations in the market, disease and more. These challenges can take a toll on the land and crops, but more importantly, they take an even bigger toll on the farmer.

“My wife and I started farming in 1978 when we joined the family operation. You couldn’t do anything wrong for the first three to five years, and then you couldn’t do anything right. We were lucky to make it,” says Commissioner of Agriculture Don Brown. “Commodity prices and land values collapsed, there was an enormous amount of foreclosure and families that had been in business for more than 100 years were no longer operating. The mental toll is just devastating.”

In the throes of a financial crisis, farmers don’t just lose their jobs – they lose their livelihoods.

“They typically lose everything,” Brown says. “They can’t feed the kids or make mortgage payments. You have to find another job and you’ve had this skill set for farming your whole life. Now, abruptly, you have to find a new skill set. Mentally, you’re a failure, and that’s all you can think about. It doesn’t take long to spiral down from that when there’s reminders all around you.”

Brown says that consumers are usually blind to a farmer’s struggle, because the food keeps coming.

Joe Harper, a fifth-generation farmer in Yuma County, also understands the mental battle.

“When the commodity prices go up, everything else follows suit. Equipment and fertilizer costs are high, and the return on investment, if there is one, is low,” he says. “My family has been here five generations. Our blood, sweat and tears have gone into the farm – it’s who we are. Maybe it’s some pride showing, but we can’t just go into town and find a new job at the hardware store. It doesn’t work like that.”

He adds that farmers endure an enormous amount of pressure because there’s no room for error.

“It’s a real challenge to maintain a positive outlook when you see things slipping away,” Harper says. “The reality of being the person that may feel responsible for losing the farm is a real heavy weight.”

Because of this struggle, the rural suicide rate in Colorado and across the country has increased in the past few decades. Commissioner Brown decided to take action for prevention in the spring of 2017, when commodity prices started to dip again.

“You could sense it was coming,” he says. “There were low commodity prices and interest rates were creeping back up. I felt like I could see the 1980s starting all over again.”

The Department of Agriculture partnered with the Colorado State University Extension, Rocky Mountain Farmers Union and the Colorado Farm Bureau to take advantage of the existing crisis hotline provided by the Colorado Department of Human Services.

“We developed training videos that helped hotline workers speak to farmers,” Brown says. “Every profession speaks a different language and this was the first time we made a push to the rural community for those who are struggling. The videos teach responders a little bit about the language of agriculture.”

The Department leaves cards with the hotline number in rural areas and at businesses across the state, in hopes that someone who needs help will make the call.

Harper was involved in the videos as well, talking about his experience and hardships. He worries that farmers may not call, but maintains a positive attitude, always making a point to talk to fellow farmers around town or in the coffee shop.

“If there’s one person that can call in, and it helps them, then it’s worthwhile,” he says.

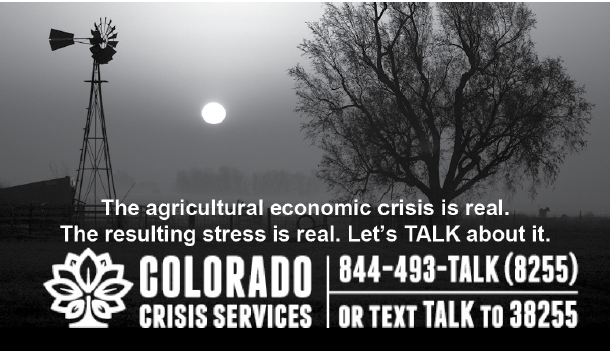

To contact the crisis hotline, call (844) 493-8255 or text TALK to 38255.